Louis Lachenal and Maurice Herzog’s Historic Ascent of Annapurna I

Louis Lachenal and Maurice Herzog aren’t new names when it comes to summiting Annapurna I, the 10th highest mountain in the world. But have you heard of them?

If not, these are the first people in the world who broke the barrier of altitude and fear of extreme mountain climbing. This historic ascent of Annapurna I (8,091 m), which marked the first successful summit of an 8,000-meter peak, occurred on June 3, 1950. No other mountaineer attempted to climb mountains above 8000m due to the limited technology, gear, and information about the mountains.

For your information, Annapurna I is considered one of the most technical and dangerous of the 8,000-meter peaks due to avalanche-prone zones and technical challenges. Many climbers have lost their lives attempting to follow in Herzog and Lachenal’s footsteps. This also makes Annapurna one of the deadliest mountains in the world.

Let’s explore Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal’s journey from France to the top of Annapurna I to make history and their sacrifice to achieve it.

Louis Lachenal and Maurice Herzog’s Planning and Exploration

Alpine mountaineering was popular in France and Europe after the World Wars. Maurice Herzog was an experienced climber and a member of the French Alpine Club. He led a French expedition team to Nepal, intending to be the first 8,000-meter peak climber.

In 1949, the French Alpine Club requested permission to undertake a major expedition. The Nepalese government then permitted the attempt to climb Dhaulagiri or Annapurna in remote northwestern Nepal. Dhaulagiri and Annapurna are 34 km apart, separated by the Kali Gandaki River.

Since Dhaulagiri appeared as a prominent white pyramid to the west, while Annapurna was hidden behind the Nilgiri mountains, they wanted to climb Dhaulagiri. Still, they found it too tricky and dangerous after an inspection mission. Hence, they quickly turned their attention to Annapurna I, even though the locals had little information about the mountain route or a viable route to the summit, and the monsoon was nearing.

Maurice Herzog was the leader of the French team. The other members were Louis Lachenal, Lionel Terray, Gaston Rébuffat, Jean Couzy, Marcel Schatz, Jacques Oudot, the doctor for the team, Francis de Noyelle, the interpreter and transport officer, and two amateurs, Jean Couzy.

Similarly, Marcel Ichac, the only person previously in the Himalayas, became the expedition’s photographer and cinematographer. With the support of sherpas and porters, unexplored maps, and minimal climbing aids, exploring different valleys lacked food supply and suffered mentally and physically.

Establishing Camps and High Camps

After research and exploration, the team reached the north face, and after exploring for five months, they were divided into three groups to find the route for climbing, but could not succeed. After reuniting at Tukusha, Herzog decided to head north, following a route suggested by a local lama towards Muktinath.

They had only 2 months left to start the monsoon, expected to start from the first week of June. They had no option but to be swift like thunder. Reuniting at Miristi Khola Canyon, taking Dr. Oudot’s medical provisions and essential supplies, they crossed the Nilgiri range. They set up a base camp at a glacier below Annapurna’s northwest spur.

Despite five days of technical climbing, they couldn’t surpass 6,000 meters. Meanwhile, Lachenal and Rébuffat searched the north face and finally discovered a possible route. This route was less technical but was an avalanche-prone zone, as confirmed by Terray and Herzog.

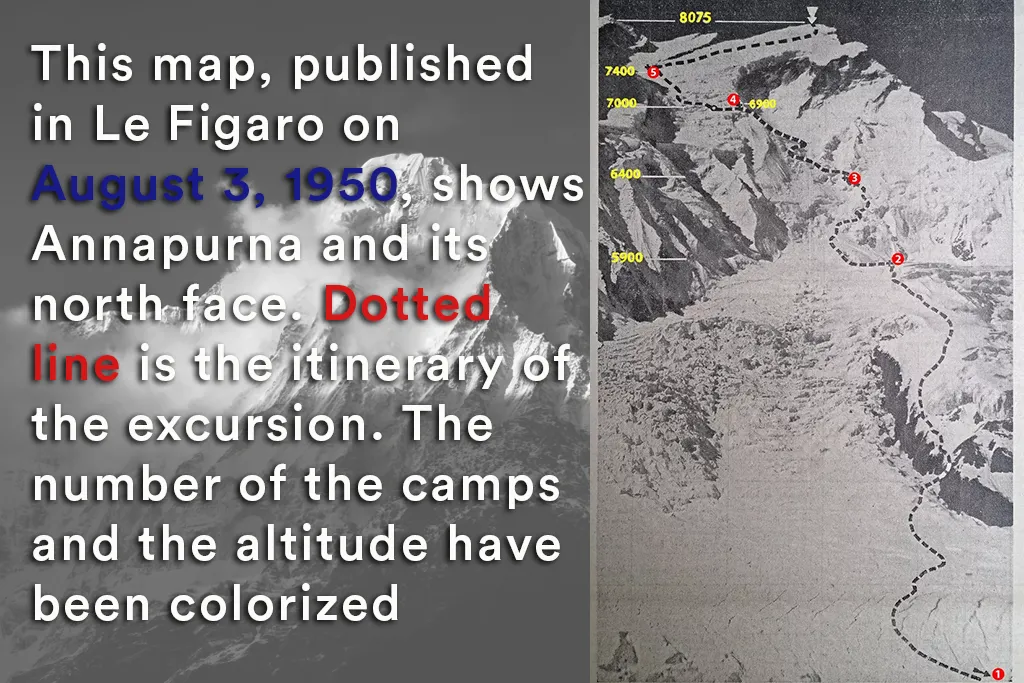

Finally, the French expedition team established Base Camp at the foot of a glacier below Annapurna’s northwest spur at 4,267 meters, where porters can reach safely and easily. They set up Camp I on the glacier at 5,110 m at a relatively gentle slope but with a slight risk of avalanches. Moving supplies from Tukucha, they established Camp II on a sheltered plateau with a little risk of snow, but heavy snowfall slowed their progress.

After crossing an avalanche-prone area, Camp III was set up among glacier seracs, and by May 28, Camp IV was established below the curving ice cliff, which they called it “Sickle.”

Difficulties in Higher Camps

As they climbed up, the lack of oxygen began to give an alert. The climbers suffered from headaches, nausea, fatigue, and extreme cold. On the way, Gaston Rébuffat and Marcel Ichac suffered from frostbite and exhaustion, resulting in being pushed back for recovery. As other climbers became exhausted, Terray selflessly carried supplies up to Camp V.

May 30, 1950: Final Push

The weather in the Annapurna region worsened, and the effects were seen in the higher camps. Maurice Herzog and Louis Lachenal required extreme exertion and much more careful planning. Other members, including Lionel Terray and Gaston, helped them to provide supplies, though they suffered altitude sickness and frostbite.

Such a critical scenario enabled Herzog and Lachenal to prepare for the final summit push from

June 1, 1950: Preparations for the Summit Attempt

With a higher motivation and determination, yet anxious, Herzog and Lachenal moved to Camp V, 7400m on a flat hill, on June 2. The whole team was exhausted, countering with physical and mental fatigue.

Both climbers knew that the altitude, thin air, and freezing temperatures could be deadly if anything went out of control. On June 2, they reached the high Camp at 7400m on the flat hill and prepared for the final summit.

June 3, 1950: The Summit Day

Herzog and Lachenal left their tent early in the morning darkness, navigating icy slopes. As they ascended, they faced fierce cold winds and thin air. Both of them had to halt frequently and try to catch their breath. Their bodies were numb due to the frozen cold in the icy Himalayas.

Unfortunately, when Lachenal approached the summit, he felt frostbite on his toes. Maurice was also suffering from sunstroke. Lachenal then asked Herzog what he would do if he went back, and Herzog replied that he would climb alone. They both agreed that no sacrifice is greater than national pride and a desire to reach the summit. Hence, they encouraged each other to continue to create an ideal day.

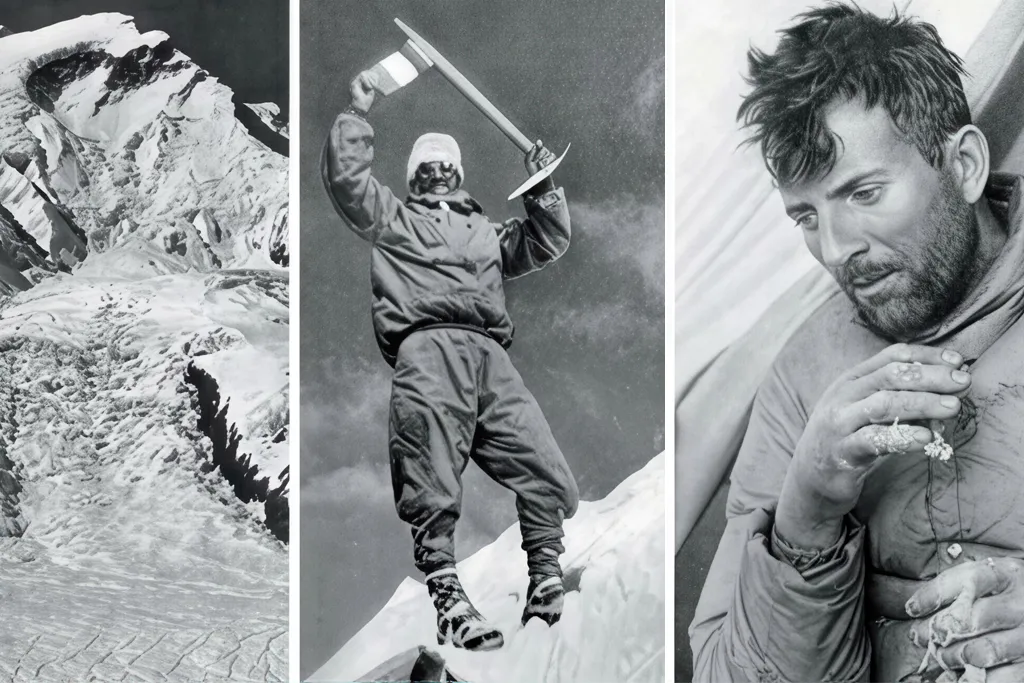

Finally, at around 2 PM, at a height of 8091 m, which no other humans had ever reached, Herzog and Lachenal stepped onto the summit of Annapurna I. They became the first humans to stand on top of an 8,000-meter peak. Both reached the top and flapped the flag

Lachenal rolled a color film, snapped the moment, and both flattered the national flag. Along with a sense of euphoria and accomplishment, both of them had feelings of dread as Lachenal’s frostbite was getting worse. They knew that the descent could be even more treacherous.

June 3-4, The Descent for Survival

The happiest moment of their life quickly turned into a nightmare. Just after reaching the summit, Herzog took off his gloves to open his pack and put them on the ground, but they slid and he lost them gloves, exposing his hands to the freezing wind. His fingers became numb abruptly and causing severe frostbite. Both of them had frostbite, making it difficult to walk and balance. Both menfolk staggered down, delirious and disoriented.

Herzog and Lachenal somehow stumble into Camp V with severe frostbite on their hands and feet. Lachenal had lost his ice axe and a crampon, and his feet were seriously frostbitten. Lionel Terray and Gaston Rébuffat assisted them by providing warmth and bandaging their injuries.

June 5-15, 1950: The Descent to Base Camp

Their frostbite was in extreme condition. They needed urgent attention. So, the team rushed for the lower camps, but the descent was intricately influenced by snowstorms and avalanches, forcing them to improvise their route. Both of them endured unbearable pain as frostbite began affecting Herzog’s fingers, and Lachenal’s toes were severely damaged.

Though they could return to base camp, the French team faced further challenges in getting medical care. They were out of medical supplies. It would take several days to reach the local settlement area and had to be carried by porters and sherpas. Both Herzog and Lachenal ultimately required amputation of multiple fingers and toes to treat frostbite. Herzog ultimately lost most of his fingers and some toes, and Lachenal also lost several toes.

At Camp II, Doctor Oudot injected them to improve their blood flow. On 7 June, all the team members descended again with Herzog, Lachenal, and Rébuffat.

As soon as they reached Camp I, there was heavy rain. On 8 June, they wrote a telegram announcing that Annapurna had been climbed. Herzog and Lachenal had to be carried on the backs of sherpas. On 6 July, they reached Nautanwa, where they got a train that took them to the Indian border at Raxaul and then to Delhi. It was only on 17 July that the French expedition team reached Orly Airport in Paris, where a cheering crowd welcomed them.

Legacy and Reflection of Feelings

With his former experience, Lachenal focused on his survival. Giving Herzog a company for his ambition and national pride, his caution about frostbite showed his strong self-preservation instinct. He had to go through a mental and physical trauma, yet showed courage and stoicism.

Maurice Herzog, on the other hand, conveyed a mixture of pride, agony, and transcendence. His quest for national honor and personal ambition kept him resilient and focused.

Maurice also documented their adventure to the peak of the Annapurna in his famous book, “Annapurna”, which became one of the best-selling mountaineering books ever. Their grit, determination, and teamwork are still honored, but the expedition also underscored the extreme risks and sacrifices inherent in high-altitude mountaineering.

Though it cost them an arm and a leg, their grit, determination, and teamwork are still honored.

FAQs

Expand AllWhen was Mount Annapurna first climbed?

June 3, 1950, was the day when any mountain above 8000m was climbed for the first time by any humans.

When was the French Alpine Club established?

The French Alpine Club (Club Alpin Français) was founded in 1874.

How difficult is the Annapurna Circuit trek?

The trek to Annapurna Circuit takes you to an elevation above 3000 meters where the temperature is low, oxygen is scarce, and the terrain is rough and risky. Thus, you can say it’s difficult to trek through the Annapurna Circuit. You must be physically fit and mentally composed to complete the trek successfully.

Can a beginner do the Annapurna Circuit Trek?

Yes, a beginner can do the Annapurna circuit trek but it might be a little challenging. You need to prepare well and be physically fit to trek for 6 to 7 hours a day in colder regions and with less oxygen.

What were the challenges they faced?

The first expedition team to Annapurna faced various challenges like

- They lack accurate maps and weather forecasts.

- There was heavy snow and an avalanche.

- They faced Severe frostbite, Herzog lost all fingers and toes; Lachenal lost toes.

- They had Limited medical supplies and emergency support.

Was oxygen used during the climb?

No, the team did not use supplemental oxygen during the ascent.

Are there books about the Herzog-Lachenal Annapurna climb?

Yes, Maurice Herzog’s book Annapurna: First Conquest of an 8000-meter Peak, published in 1951 AD became a bestseller and is still considered a classic in mountaineering literature.

Can modern climbers follow the original route of the 1950 ascent?

Not easily. The 1950 route is rarely used today due to avalanche risks and changes in the glacier.

Did Maurice Herzog lose his fingers and toes after climbing Annapurna I?

Yes, he suffered severe frostbite and had most of his fingers and toes amputated.

How dangerous is Annapurna compared to other 8,000-meter peaks?

Mount Annapurna is one of the deadliest mountain, with a high fatality rate due to frequent avalanches and technical challenges.

How did the 1950 Annapurna expedition influence Himalayan mountaineering?

The 1950 Annapurna expedition opened the door to 8,000-meter climbing and inspired a generation of climbers worldwide. This is the milestone for today’s mountaineering industry.

How difficult was the Annapurna I expedition in 1950?

1950 was the year when mount Annapurna was climbed by humans for the first time. There were no maps, no fancy gear, and extremely difficult to ascend with many unknowns.

What gear did the climbers use during the 1950 expedition?

In 1950, they used very primitive (by today’s standards) gear, basic ice axes, crampons, wool clothing, to climb Mount Annapurna.

What happened to Louis Lachenal and Maurice Herzog after the climb?

Herzog became a national hero and politician. Lachenal returned to climbing but died in a skiing accident in 1955.

What role did the French Alpine Club play in the 1950 ascent?

The French Alpine Club including organized, funded, and selected the team for the historic expedition of 1950.

Other members Lionel Terray and Gaston Rébuffat, helped establish camps and support the summit push.

What route did Herzog and Lachenal take to climb Annapurna I?

Herzog and Lachenal climbed via the north face and northwest ridge. This route is very dangerous and rarely used nowadays

Who were Louis Lachenal and Maurice Herzog?

Louis Lachenal and Maurice Herzog were French mountaineers from the French Alpine Club. They were the first people to climb Mount Annapurna in 1950.

Herzog was the team leader, and Lachenal was a skilled alpine guide and climber.

Related blog posts

Discover a choice of tourist destinations loved by most of our visitors. Whether you're on a jungle safari to spot rare animals or walking through a world heritage site, these well-planned itineraries cover the major highlights of Nepal.